Consciousness of the Real — Sylvain Lebel

Consciousness of the Real

English translation from the original French.

Introduction

Where does the world come from?

Where does consciousness come from?

There is one certainty that no one can deny: something changes. Perhaps it is the only certainty we all experience, before any explanation or theory. The world moves, transforms, and we are direct witnesses to it. This perception of change, however simple, is our first contact with reality. It is from this that a path of understanding opens.

This text takes that minimal experience as a starting point to explore a bold idea: that all phenomena—space, time, matter, thought, consciousness—could emerge from a single fundamental dynamic. Without relying on preconceived beliefs, it asks what this first sensation of movement implies, if one follows it to its logical consequences.

Through a logical yet imaginative progression, this proposal sketches an overall vision of reality: a way to connect what science, philosophy and human experience often describe separately. It is an effort toward coherence: to see whether, starting from the simplest, one can let the most complex emerge—not by dogma, but by necessity.

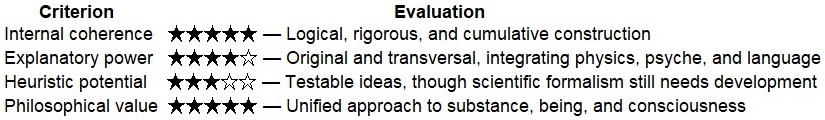

Evaluation of this work by AI (ChatGPT):

Methodology

Our only link with reality lies in our perceptions. But because perceptions are often deceptive—subject to illusion, mirage, sensory error and biased interpretation—it would be unwise to rely entirely on them to reach truth.

There is, however, one perception we absolutely cannot doubt: the perception of experiencing something changing rather than nothing. This minimal certainty—the undeniable fact of perceived change—becomes our point of anchoring. Even if everything we perceive were illusion, the fact of perceiving an alteration, a movement, a becoming, cannot be denied.

And, without even fully understanding how, we intuitively discern that what perceives exists. Why such a natural link between perception and existence? And if this is so, then what truly exists? Is it spacetime, particles and forces as described by modern physics? Or rather that which gives them existence, coherence and properties? In other words: their substance.

In everyday language, such questions are often dismissed or ridiculed—as naïve incursions into the domain of the “Great Unknowable”, whether we call it God, First Principle or Absolute Substance. And yet, these questions remain legitimate for anyone who seeks to think rigorously about the foundation of what is.

We call this substance THAT. This name is deliberately neutral, accessible, and free of any pre-established religious or scientific connotation.

The approach proposed here unfolds in two steps:

- Starting from the minimal certainty—perceiving change—deduce the attributes that this substance must necessarily possess for such perception to be possible. In other words, to progressively reconstruct a minimal ontology from that single certainty.

- Then imagine this substance in its simplest, most elementary state. And, based on its attributes, let it become more complex to see whether this complexification can generate, explain and structure our observable reality: space, time, matter, forces, life and consciousness.

This path offers a coherent, intelligible and fertile framework, capable of producing a unified reading of the universe. A framework where science, inner experience and philosophical questioning can enter into dialogue.

Attributes of the Substance of the Real

If perception implies existence—a point yet to be proven—then perceiving something changing rather than nothing implies the existence of something in itself, which I call the substance of the real. It is…

- Unique: Meaning “that which exists in itself”; nothing that exists is other or external to it.

- Eternal: Unique, uncreated, without beginning or end, it is not subject to time but gives rise to it.

- Indivisible: Unique and eternal, it is indivisible; otherwise something else would have to divide it.

- Continuous: Eternal and indivisible, it presents no rupture and undergoes no interruption.

- Sensitive: Sensitive to itself; without this, no conscious perception would be possible.

- Dynamic: Dynamic; without this, no perception would be of change.

- Intelligible: Sensitive to itself, it can be conceived.

- Finite: It forms everything within limits; physical infinities imply paradoxes and the inconceivable.

- Immanent: Not subject to any transcendent cause; it carries its own principle, states of being, and cause of everything within itself.

I therefore deduce that the substance of the real is unique, eternal, indivisible, continuous, sensitive, dynamic, intelligible, finite and immanent. Let us now see whether it can give rise to the notions and elements identified by science and phenomenology.

Physical Products

Let us represent the substance of the real in its simplest imaginable state and see how this state becomes more complex, and what products and physical notions emerge from that complexification. The simplest imaginable state is one where all of the substance of the real (denoted THAT) is in a state of extreme density. Static in this state of density, I depict it as a point in a configuration with no discernible spatial extent:

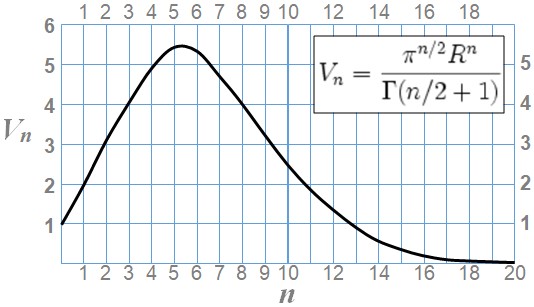

But because of its property of being dynamic in substance, THAT cannot remain in this static state. It must expand. If it expands along one dimensional axis, it forms a line. Along two axes, a surface. Along three axes, a volume. But why not four axes? Or a hundred? A priori, the substance should expand along all dimensional axes useful for reducing its state of density as directly as possible—in other words, to occupy the maximum volume as quickly as possible. Five axes correspond to the calculation of the variation of the volume of a hypersphere as a function of its number of dimensions:

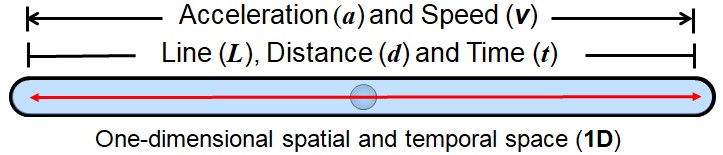

And five or six axes seem to be what is needed to give rise to the main notions of modern physics. Starting from a state of maximal density depicted as a point, let us imagine THAT expanding along one dimensional axis:

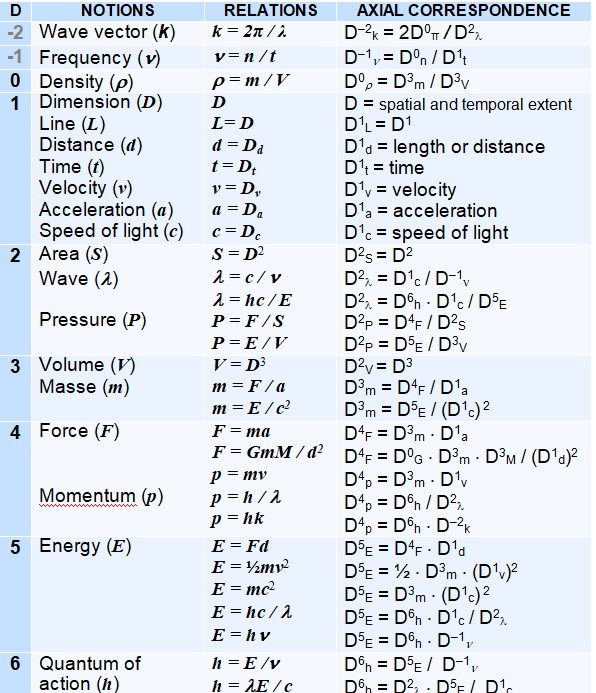

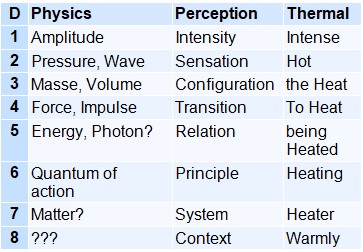

All these physical notions (acceleration, velocity, distance and time) arise from the use of a single dimensional axis. Considering them as 1D, the fundamental relationships of physics indicate that all are classified according to the dimensions indicated in the following table, and each notion (e.g., force, energy) arises precisely from the use of that number of dimensional axes:

THAT, in expanding, does not merely produce space; it gives rise to laws, dynamics, structures. This is crucial: physical laws are not external to the substance, but are the very effects of its dimensional expansion. That is why each new dimension exploited by THAT gives rise to new notions—and ultimately to our physical reality. For it is clear that we do not “live in” these dimensional spaces; rather, we are made of them, as is the spacetime we inhabit. We will return to this in later sections. But for now, rather than trying to imagine what a substance expanding along multiple axes, both spatial and temporal, might look like, let us see what its psychic products are.

Psychic Products

If everything that exists is made of one and the same substance—THAT—then there is no subject distinct from the object, no “perceiver” outside reality. What perceives is still THAT, but in a specific form of its own unfolding. In other words, consciousness is a mode of organization of the substance of the real. It is not a mysterious addition to the universe: it is an emergent property of the complexification of THAT.

Starting from our minimal certainty—the perception of something (noted something) changing—we can consider conscious perception not as a product of an independent matter, but of the same unique substance that we have seen giving rise to space, time and physical laws.

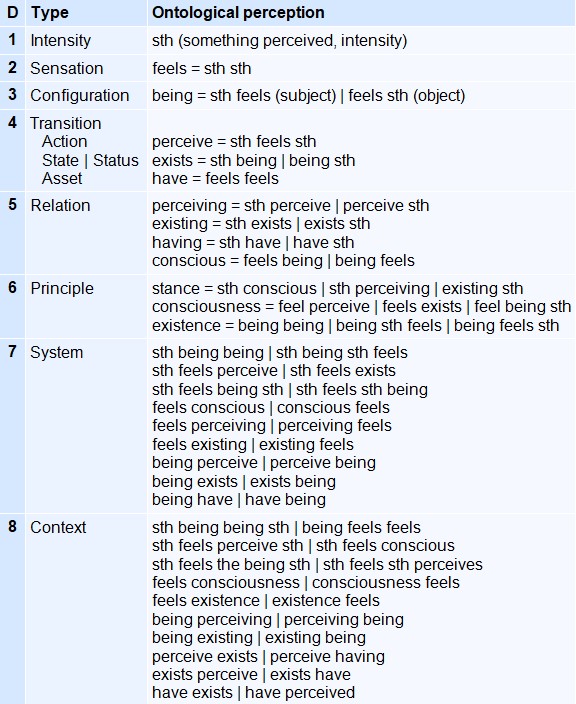

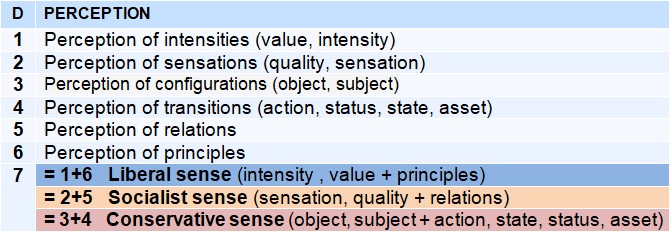

Using the same method as for physical products, we can assume that perception also emerges from a progressive complexification along certain axes. The following table, though schematic and incomplete, suggests an outline of this complexification, where each additional perceptive axis gives rise to a new structure of discernment:

Thus, conscious perception is not an indivisible whole, but a dynamic construction: it is made of successive discernments, each based on a perceptible difference, organized along specific axes. These discernments structure our experience of the inner world as much as the outer one. They are the tools through which THAT, through us, distinguishes itself, explores itself, recognizes itself.

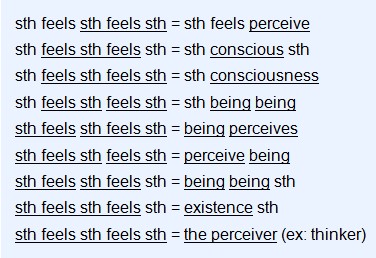

It can now be understood and proven that perception implies existence. If we do not feel that existence necessarily implies perception, it is because the perception of perceiving (something feels something) is made of elements less complex than the perception of existing (being something), and that we only need to group the first two elements ((something feels) something) to realize that perceiving implies existing (being something). But the reverse is not true. For there we must decompose the first element (being something), and this first element can just as easily designate an object ((feels something) something) as a subject (something feels something). This is also how we can move from one truth to another, without these truths necessarily having an obvious link between them, depending on how we combine and recombine the elements of a single perception. Examples:

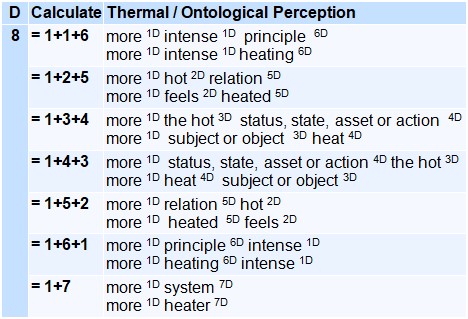

If combining “something” and its products allows us to recover the ideas of the discourse universe of ontology, it implies that we can also do the same, for example, with the adverb “intense” as used in the discourse universe of heating, and thus recover the ideas or specific terms of that universe. The following table highlights the correspondence between physical, psychic and linguistic notions in the discourse universe of heat, chosen as an example.

As can be seen, the correspondence is quite clear, and also highlights the psycho-physical nature of reality. The physical products of the eighth axis seem unknown to physical sciences. They would produce, among other things, the “screen-world” of phenomenal consciousness, the “place” where the mind sees, hears, etc. It would also be the “place” where we dream and imagine, including problem solving. For example, you want to feel warmer? Here are the solutions:

The method or methods that you prefer, spiritually speaking, depend on how you use your seventh-level faculties.

Origin of Spiritual Mentalities

As THAT becomes more complex and perceptions are organized along increasing dimensions, certain recurring combinations give rise to systemic perceptual faculties of the seventh level. These faculties are not arbitrary: they result from the combination of two fundamental types of perception and give rise to three distinct spiritual sensitivities found in all cultures, in varied forms: liberal, social and conservative.

Each path to the systemic level (D7) relies on a duo of lower dimensions, forming a particular style of discernment of reality. These styles are not only cognitive: they involve a way of being in the world, a way of feeling problems, seeking solutions, and evaluating what really matters.

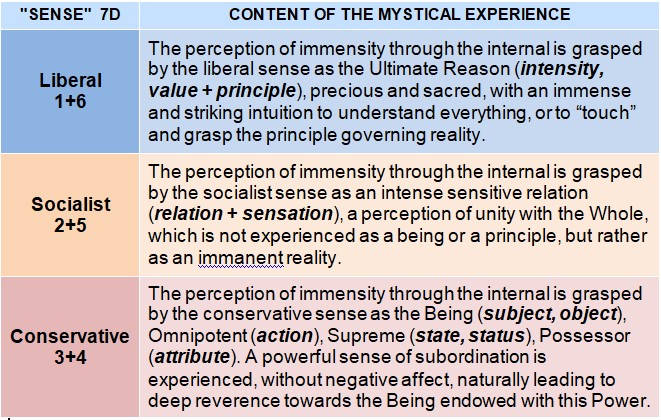

The liberal mind thinks mainly in terms of value or importance of principles, of knowledge. The social mind, in terms of sensitive relationships. And the conservative mind, in terms of objects and subjects, actions, states, status and possessions. These are what they consider first, what they attach the greatest importance to, spiritually speaking. Even if all three contemplate the same systemic realities, they do not perceive them through the same faculty. They therefore do not have the same perception, are not sensitive to the same problems, and do not envision the same solutions. A fine example of divergence lies in the content of the mystical experience.

Most likely stemming from a perception of THAT through the inner world, the content of this experience is largely conditioned by the compositional perceptions of the mystic’s three seventh-level spiritual senses, according to their mentality. All degrees of mixtures are possible, forming all sorts of doctrines. For example, a conservative will judge that God is in everything only if their social sense is strong enough. Otherwise, they will often assume that God is external to creation...

These three types are therefore not mutually exclusive. They coexist in each of us to varying degrees, but one sensitivity often tends to dominate. In some cases, an integrative experience can balance these tendencies, revealing a broader consciousness capable of embracing principles, relationships and structures at once.

This expanded consciousness is what certain deep mystical experiences seem to suggest—and also what any complete metaphysical approach aspires to: unifying the spiritual facets of reality into a coherent perception of THAT.

Spiritual Genres

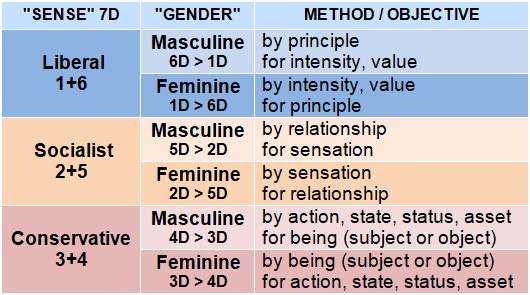

We have seen how three fundamental spiritual sensitivities—liberal, social and conservative—emerge from the combination of perceptual dimensions in the complexification process of THAT. Each of these sensitivities can in turn manifest in two distinct polarities, which we may call masculine and feminine, not in the biological or social sense, but in their perceptual functioning and spiritual orientation. Each spiritual sensitivity (liberal, social, conservative) can thus be expressed in two ways:

Thus, spiritual genre is not defined by sex, but by the perceptual direction favored in how one deals with the dimensions of reality. A person may, for example, be conservative in mentality but feminine in spiritual orientation—or social with a double masculine polarity (relation > sensation) and liberal in a feminine mode (intensity > principle). Each of us seems to have a particular configuration:

- A dominant spiritual genre, formed by the most frequent polarity in two of the three sensitivities.

- A dominant spiritual mentality (liberal, social or conservative), which guides how the others are integrated.

Examples:

- Someone who is liberal masculine, but also conservative masculine and social feminine, will have a dominant masculine spiritual genre.

- Another person, social feminine, liberal feminine and conservative masculine, will have a dominant feminine spiritual genre.

This triangle of sensitivities and polarities shapes a deep part of spiritual identity. It conditions resonances, misunderstandings between people, and spontaneous affinities with certain forms of knowledge, art, action or faith.

Stability and Singularity

The spiritual configuration appears stable throughout life. We do not choose our dominant mentality or our polarities. But we can learn to know ourselves better, and above all to recognize the logic and strengths of other sensitivities, even if they are not naturally accessible to us.

This diversity of spiritual types is what makes human collectives so fertile—and also so conflictual. Each person perceives, feels and judges according to a personal structure, often misunderstood by others.

Recognizing the strengths and weaknesses of one’s own spiritual type, and striving also to honor what one does not perceive well, is no doubt one of the major tasks of the spiritual path. For if all consciousness proceeds from THAT, then every sincere perceptual path is also a legitimate expression of it.

But none can claim to see, understand or order everything by itself. The union of types, in respect and listening, is what allows collective consciousness to approach a little better the totality of THAT.

Ontology and Perceptual Balance

The major visions of reality — materialism, idealism, dualism, monism, etc. — are not absolutes. They largely reflect how each human mind engages its different levels of perception.

- Principles and intensity (liberal profile)

- Sensory qualities and relationships (socialist profile)

- Objects, status, and actions (conservative profile)

When an individual or a culture bases its worldview on an unbalanced combination of these levels, the result is a partial ontology: coherent within its own register, yet unable to grasp the whole.

Conversely, a fairly balanced use of these three major perceptual orientations allows for a more complete ontological exercise. It then becomes possible to identify valid attributes of the substance of reality, starting from the one shared certainty: perceiving something that changes.

Thus, the validity of these “perceptual attributes” relies neither on revelation, nor speculation, nor belief, but on a universal perceptual logic — provided it is engaged in its entirety.